Sanitized Children

The body temperature of Japanese children is consistently dropping. This is a fact first brought to light around 1980. Today, compared to the post-war children born after 1945, data shows that children’s temperature has dropped by nearly 2.5 degrees Celsius. Considering the fact that the immune system functions 30% less with each degree dropped, this situation is becoming more serious than previously imagined. Anime Director Koji Morimoto further points out that especially children who live in cities are kept climate-controlled regardless of the season, and are grown like sterile cultures in a disinfected environment.

“You don’t get to build your antibodies from a young age unless you are out there trying out things like eating dirt. Yet, the places kids play these days are paved with concrete and all the weird things and curious spots are destroyed one after another. Adults clean it up nicely and decide for the kids where to play, but kids complain that they don’t want to play in such a cleansed place. At the very least, they should be able to choose where they play. Maybe that’s why kids don’t want to go outside anymore.”

“For children, places that are left unkempt are superb playgrounds. I think taking away all the chaos and strangeness from cities results in more aggressive behaviors in children. They also need to let out their curiosity bit by bit that they are holding in. If not, they will eventually explode. I feel like that is why bullying and juvenile crimes are getting more and more malicious. I don’t want to criticize modernization in its entirety, but leaving behind something untouched is also very important.”

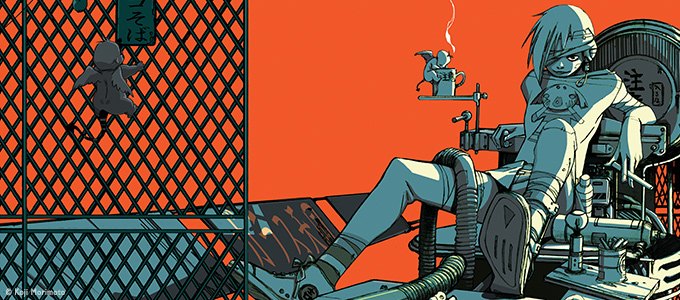

For modern children, the only playground (that seems) left untouched perhaps, is the internet. The web space could still pull you into the chaos of the dark and maze-like back alleys. Director Morimoto’s creations also feed that need. It is the internet after all, that allows the new generation from all around the world to come across Director Morimoto’s classic works, captivating them with the terrifying yet euphoric feeling they can’t seem to find anywhere else.

“I don’t feel like the overseas fans are drawn to my work because of the representation of Japan. It’s something more like a sense of feel or touch that they are after. That thing we all experience as children, that scary something, wanting to know what’s on the other side of the wall but being not tall enough to actually get to see it…. Those things.”

“The back alleyway, in that sense, symbolizes the adventurous heart. When you turn a corner, a different view suddenly reveals itself. I like that kind of magic. On the streets there were vendors selling lots of weird things. In the past, there were plenty of mysteries such as that in rural areas and even in the cities.”

“The same goes for the mountains. When walking on an animal trail, you can’t see far ahead and your heart starts racing. You hear a creepy sound and come across odd-looking insects and plants. Mountains truly embody these mysterious details. So, I can tell right away when someone is creating a scene from a mountain. If you’ve never been to the mountains, none of those things come out in the pictures. On the other hand, if I see even a glimpse of it, I know ‘this guy gets it.’”

The vivid memories from spending his youth in the deep woods of Wakayama, going home only when it got too dark to see, adds a musty air to his stylish and often urban imageries. The director returns at least once a year to visit his hometown Kimino, where the distinct sounds and sights are only familiar to residents, and are left somewhat untouched.

“My favorite spot still to this day is where I can see the whole circumference of the valley. There is a small bridge over the river from where I can see my house on my way home from school. It’s upstream, so it’s quiet, and therefore the flood of sound is incredible. I know which house is receiving guests that day just by the sound of a car coming.”

“Because it was a rural community, we all played and learned together, from preschoolers to teenagers, all together. We shared a lot of knowledge and even challenged kids that were ten years older. It was obvious that we will lose to older kids, but it hurt just the same and led to new strategies for beating them next time.”

“There weren’t any things laying around, so we never expected anything more. We made everything from scratch. We found wood and poked holes in it to make cars, and created a tree house and played in it. Growing up like that, it becomes natural and we never hesitated to share or explore ideas together. As children, we were always discussing and trying to figure out together how to make it happen.”

In order to preserve the vistas of his old hometown, as it too experiences the gradual change of time, Director Morimoto has started participating in revitalization activities in recent years. He is planning an event that will start from his alma mater high school that has been long shut down. The event emphasizes “inconveniencing” and “making you work hard” to get to the destination. Leading participants through narrow trails that are inaccessible by cars, and allowing parents and children to enjoy, together, that rare effort.

Children who have lost degrees of their body heat should be taken outside. The adults who should be teaching them the smell and taste of dirt and the allure of back alleyways, are in fact, big children who have been sanitized themselves.

Way ahead of us, a glimpse of adolescent Morimoto skips ahead on the path and turns around… beckoning us to follow his lead.

(Interview: Manami Iiboshi, Translation: Mika Anami)